Taming Monoliths without Microservices — Rubyconf AU 2019 Talk

You can also see the slides on SpeakerDeck.

This talk is an adaption of a talk I gave at GoRuCo 2018. This talk tells the story of a growing engineering organization continuously adding structure to their large Rails codebase.

The talk concludes with 4 concrete tactics you can employ in your day job to help ease the transition to a more modular world.

Part I: About Me

My name is Kelly Sutton, I work as a software engineer in San Francisco. I live with my fiancé, Amelie, and our dog, Greta. I work for a company called Gusto, which does payroll, benefits, and HR software for small businesses.

Gusto serves about 1% of small businesses in the US. We operate mostly out of a single monolith and have over 80 engineers. The platform moves more than $1 billion per month for tens of thousands of businesses.

Payroll software is a careful combination of time, geography, money, and people. Folks need to be paid on time for the time they worked. Single tax jurisdictions can be as small as a city block, or as large as the country. Employees need to be paid accurately to the cent, otherwise the you’ll make the IRS unhappy.

Finally, all of this is being run by people. We are all human and to be human is to make mistakes. A payroll system must be designed to be malleable, and to be able to correct mistakes.

Which brings us to an important caveat in this talk: Gusto might make different tradeoffs than your business. One of the biggest tradeoffs we make is the tradeoff between correctness and performance. We will always choose accuracy and precision over speed. This comes into play when modeling our data or choosing caching schemes.

Every business is different, so some of the things ahead may not apply to you.

Part II: Breaking the Monolith

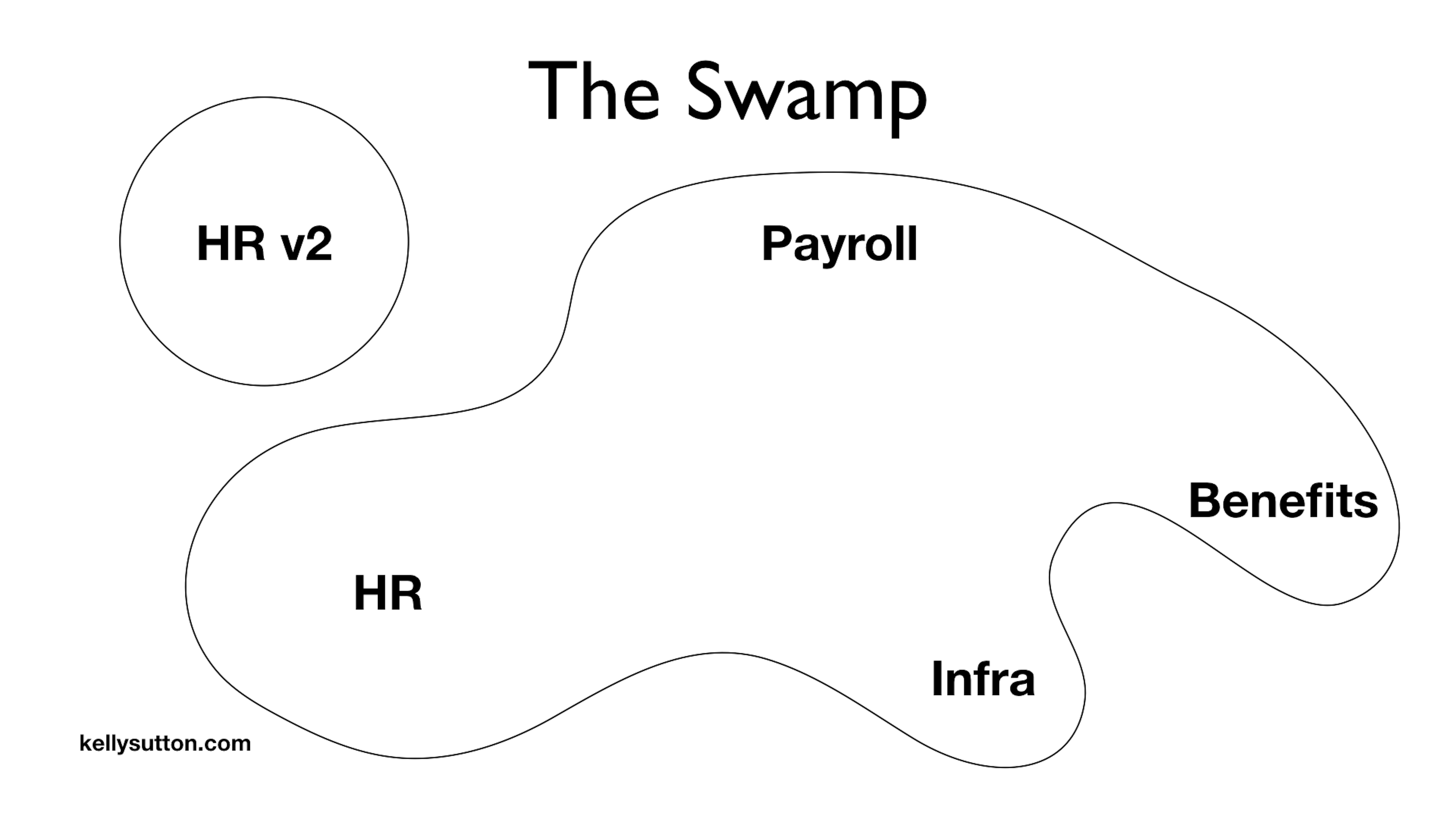

Before we discuss how to break a monolith, we need to describe it. I like to call a large monolith a Swamp. You may know it as the Ball of Mud.

I find Swamp a better terminology, because it is something you’re in. A Ball of Mud is something that is just over there, on a pedastal. As you work in a Swamp, things become slower and slower. What used to take milliseconds now takes seconds. What used to take seconds now takes minutes.

Here’s what our Swamp looks like. It’s all in the same monolith with different parts in charge of Payroll, Benefits, HR, and general Infrastructure.

The seams between each of these domains is fuzzy. Models and database tables are shared. None of the interaction patterns are well-defined. Oftentimes you just reach directly into the other domain’s tables if you need information from them.

It’s not long of operating in a world like this before someone comes back from a conference and says, “Let’s extract a Service!”

You want to get back to that rails new feeling, so your team talks it over and you decide you’ll extract a new HR service.

So you new up an HR v2 service and get to work.

You work with the team to slowly connect the existing functionality to the new service. You meticulously move over behaviors one by one.

But this ends up taking a lot longer than you thought. Furthermore, the HR responsibilities were much larger than you thought. It soon becomes someone’s full-time job to track “What’s in the original HR system and what’s in HR v2?”

Time drags on and the project feels like it will never ship. PMs and other stakeholders are breathing down your neck, so you eventually call things done enough. You decide to ship what you’ve got and move onto the next project.

But while you’ve moved over 90% of the behavior to the new system, the old HR system still is doing critical work for the company. Otherwise, you would just delete it. You need to keep the old HR system around.

And now you’re in a worse situation that you started with. You now have 2 HR systems!

This is exactly where tribal knowledge comes from. You have 2 ways of doing something, and knowing which does what is a learned skill instead of something that is self-evident. The question Where are Social Security Numbers stored? now is something that has a learned answer. Oh, we didn’t get around to moving those so those are still in the Old HR system.

These questions make it more difficult to onboard as a new engineer, and make maintaining and reasoning about the system difficult for seasoned engineers.

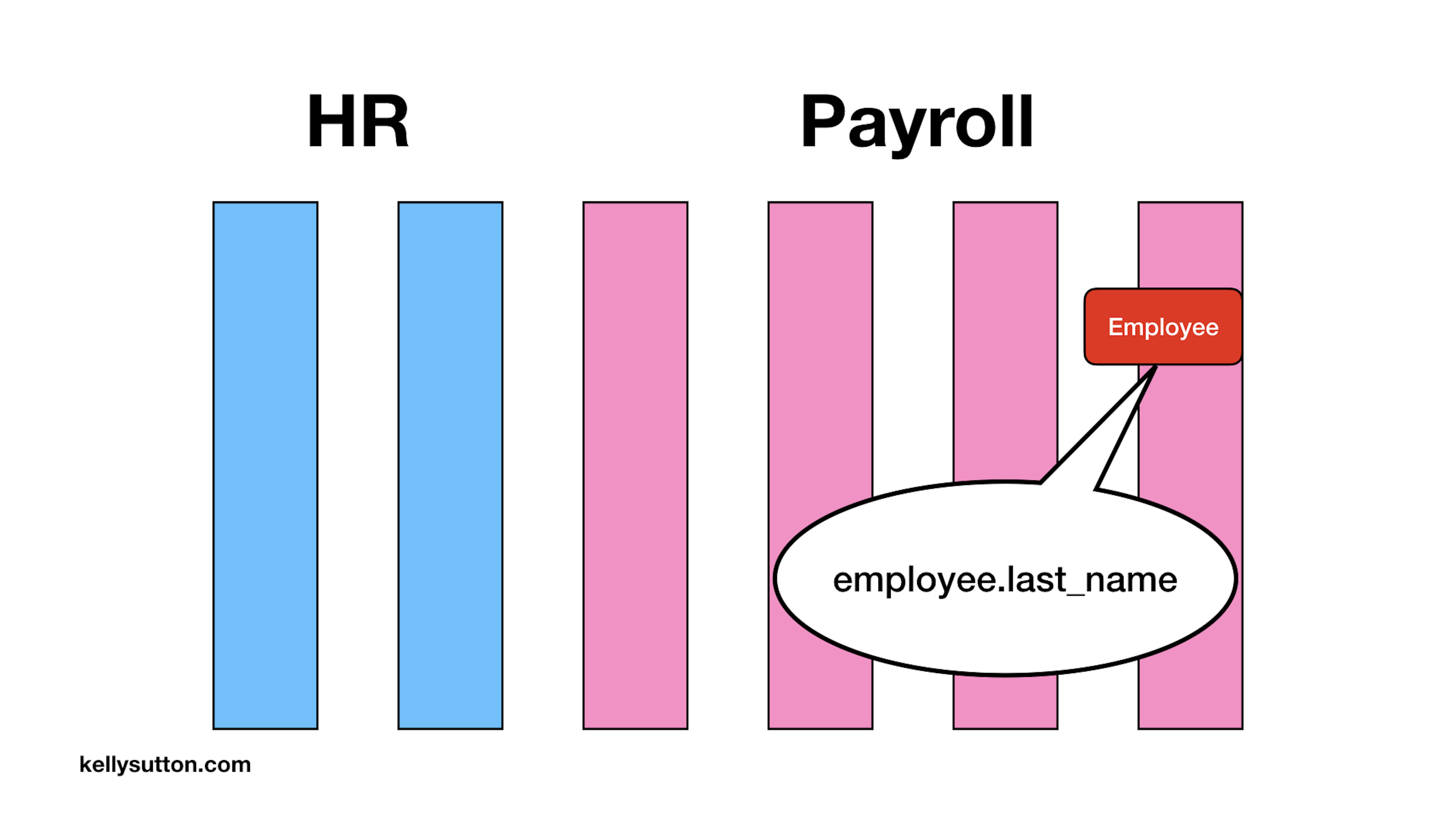

So let’s move back to our Swamp. We’ll take a slightly different view here and we’ll look at one code path through the system.

Each vertical bar represents some class or layer in the system. Each one could be a controller, a service class, a presenter, or a view. It doesn’t really matter. We have an Employee ActiveRecord object which we signify using this red square.

Let’s pretend that the HR system is sending information to the Payroll system for the purposes of putting a last name on the paystub.

The employee object is passed all the way down into the depths of the Payroll domain, where the last name is pulled off of the record.

Why would this be a problem? In a small application, it’s not! Code like this is probably fine.

But what happens when someone gets married and changes their last name, or they transition and change their first name? Do the names on their historical paystubs change? The expectations of different government agencies will want different names at different points in time.

So how can we get around this?

We’ll start by creating a conceptual boundary between our two systems, illustrated above using the yellow bar. This boundary might not exist in the code, but is just the general area where a team thinks an API should exist.

Now we’ll do the work to use that boundary. Here is the point in the code where we’ll turn our red ActiveRecord object into a value object or Whole Value, indicated by the green box.

We now have a point in the code where our rich ActiveRecord object becomes something new entirely. We might call it a PayrollEmployee. This new object is a Plain Old Ruby Object (PORO) and is nothing more than just a bundle of values.

We again send this object down the stack and pull of the last name.

You might be thinking, haven’t we just moved some things around? Indeed, we have. But we’ve importantly done a few things that we didn’t have before. By not passing the HR employee record around, we’ve reduced the coupling between HR and Payroll. This should make it easier for the two domains to change in the future.

Furthermore, we’ve given a name to a concept that was hiding in our system: the PayrollEmployee. This is because we’ve realized the HR and Payroll concepts of an employee are different. For Payroll, employee information is little more than just metadata: It’s a label that gets printed on your paystub. For HR, it’s much more about the person as an entity and how they change over time.

As we practice this more and more, we’ll come up with many value objects to capture the interactions between our two systems. As we iterate, the relationship between the two systems becomes clearer. Because we are not passing around rich ActiveRecord objects—each having a database connection and relationship graph ready to traverse—our systems are less coupled.

Now this is a little weird and not typical for your average Rails application. In fact, we might see an ActiveRecord turned into a value object only be turned once again into a different ActiveRecord object in the destination domain. But we’ve unshackled the two domains from each other, and they can now move independently and with confidence.

This practice injects a good deal of structure into our application, and even makes the switch to microservices easier down the line.

Which brings us to the concept of Conceptual Compression. @dhh mentioned this term in his Railsconf 2018 keynote. Rails does a great job of “compressing” concepts that we don’t need to care about until necessary.

Chances are, your Rails app doesn’t require a DBA or anyone else with a strong knowledge of SQL. ActiveRecord and its underlying technologies give you safe defaults that will work for the first few years of your application. Your app may never grow large enough to have concerns with ActiveRecord’s ability to work with a database.

This is a great thing! Worrying about things before you need can distract a company from focusing on the needs of the business.

But if you are in the process of breaking apart your monolith, you likely need to embark on some Conceptual Expansion. You and your team will need to carefully examine the different concepts that Rails compresses to see which are compatible with your architecture goals.

The following are some of the non-obvious tips we’ve found to expand some of the concepts that Rails compresses as you break apart your monolith.

Part III: Tactics

These tactics are things that we’ve found at Gusto to be important considerations as our Rails app grows. Take them with a grain of salt, they might not be appropriate for your situation. As always, discuss these with your team before enacting them outright.

As your code base grows, question Rails bidirectional relationships. For many of us, wiring up bidirectional relationships is muscle memory.

Here’s how that might look for a simple Company and Employee relationship.

But we’ve found ourselves asking if we really need relationships in both directions.

Although we are not importing and exporting code, we still draw dependency graphs with every line of code we write in Ruby and Rails.

Each bidirectional relationship creates a circular dependency. Circular dependencies can flatten your layered architecture and muddy your object graphs. It’s for this reason we ask if we keep our object graph simple by omitting some bidirectional relationships.

When traversing the edges or arrows between domains or layers of your application, use Value Objects.

Let’s take a look at an example:

Here we have a simple service class, CompanySignedUp, that handles an operation of what to do after a company has signed up for our app. This looks like a pretty normal service class in a growing Rails app.

This service class sends off an email using CompanyMailer and tracks some stats via StatsTracker.

But we’ll find that each of these 3 classes, CompanySignedUp, CompanyMailer, and StatsTracker are all coupled to the shape of company. This means that should the Company class ever change, we will need to make changes in 3 parts of our code. This is Shotgun Surgery.

So instead we want to “bail out” of our rich objects into values at the right times. At Gusto, we’ve found the sooner the better, generally.

Here we want to peel off just the values that CompanyMailer and StatsTracker need to do their job. In this case, we only need user_first_name, email, and company.id.

Now should the shape of company ever change, we only need to make a change in a single class: CompanySignedUp. If we find our method signatures getting too long, we can introduce parameter objects.

Callbacks are a crucial part of Rails. They give us an expressive interface to perform an action after another. Unfortunately, Rails callbacks can flatten layered architecture.

Let’s see how:

In this code we have a simple callback on a Company class that sends an email using CompanyMailer. (Let’s not worry about the fact that sending an email should be a background job here.)

If we look at the implicit dependency graph that we’ve drawn here, we’ve got a circular dependency. Company knows about CompanyMailer, and CompanyMailer knows about the shape of Company. These circular dependencies are exactly what makes an app difficult to maintain.

If you zoom into the Ball of Mud, you’ll see thousands of these circular dependencies. Callbacks make it very easy to create these circular dependencies.

Rather than reaching for callbacks, we look to use simple service classes instead to encapsulate behavior. Here, we’ve moved the the logic that was contained in a model and a mailer into a CreateCompany service class that wraps our behavior.

If we now look at the dependency graph we’ve drawn, we have another node! But we have also eliminated the cycle.

We’ve found that it’s better to introduce a new node into your dependency graph than to introduce a cycle when designing your applications. This keeps the structure of the application simpler and easier to change.

Finally when breaking apart your monolith: move slowly. For Gusto, extracting a single service required hundreds of Pull Requests over several months. It takes time and trust in your team.

Part IV: Wrap Up

Breaking apart a Rails monolith is a risky endeavour. We derisk the activity by constantly breaking down our work into the smallest possible units. We set a vision and set sail. We trust our teams to do the right thing, and we have buy-in from the business.

Thanks!

References

- Bernhardt, Gary. “Boundaries.” 2012.

- Bernhardt, Gary. “Functional Core, Imperative Shell.” 2012.

- Evans, Eric. “Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software.” 2003.

- Fowler, Martin, et al. “Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code.” 1999.

- Feathers, Michael. “Working Effectively with Legacy Code.” 2004.

- Hickey, Rich. “Simple Made Easy.” 2011.

- Hickey, Rich. “The Value of Values.” 2012.

- Scott, James C. “Seeing Like a State.” 1999.

- Searls, Justin. “My Favorite Way to TDD.” 2017

- Spolsky, Joel. “Things You Should Never Do, Part I.” 2006.

Another thank you to RubyConf AU for having me out to present. It was a truly remarkable conference with many talented speakers. All of the talks are available on YouTube.