Moving on from React, a Year Later

It’s been a busy year for Scholarly. At this time last year, we were just closing our first contracts after having been in business for 6 months. Since then, we’ve raised a seed round, achieved SOC 2 Type II compliance, grown our customer base substantially, and expanded our team. On the technical side, we continue to cut out vectors of accidental complexity by keeping our technology choices simple.

One of the blog posts I wrote last year, Moving on from React, resurfaced in conversations on Twitter this week. This post is a retrospective on what’s changed since we wrote that post and reflects on that decision.

Where are we today?

Since writing the original post, our technology stack has remained largely consistent: Rails, Stimulus, MySQL all in a server-rendered context. We use Turbo and ActionCable at times to add an extra layer of interactivity and responsiveness when required. With Turbo, we utilize prefetching and page caching. This stack feels perfectly suited to our business. You can best think of Scholarly as an HR platform for universities.

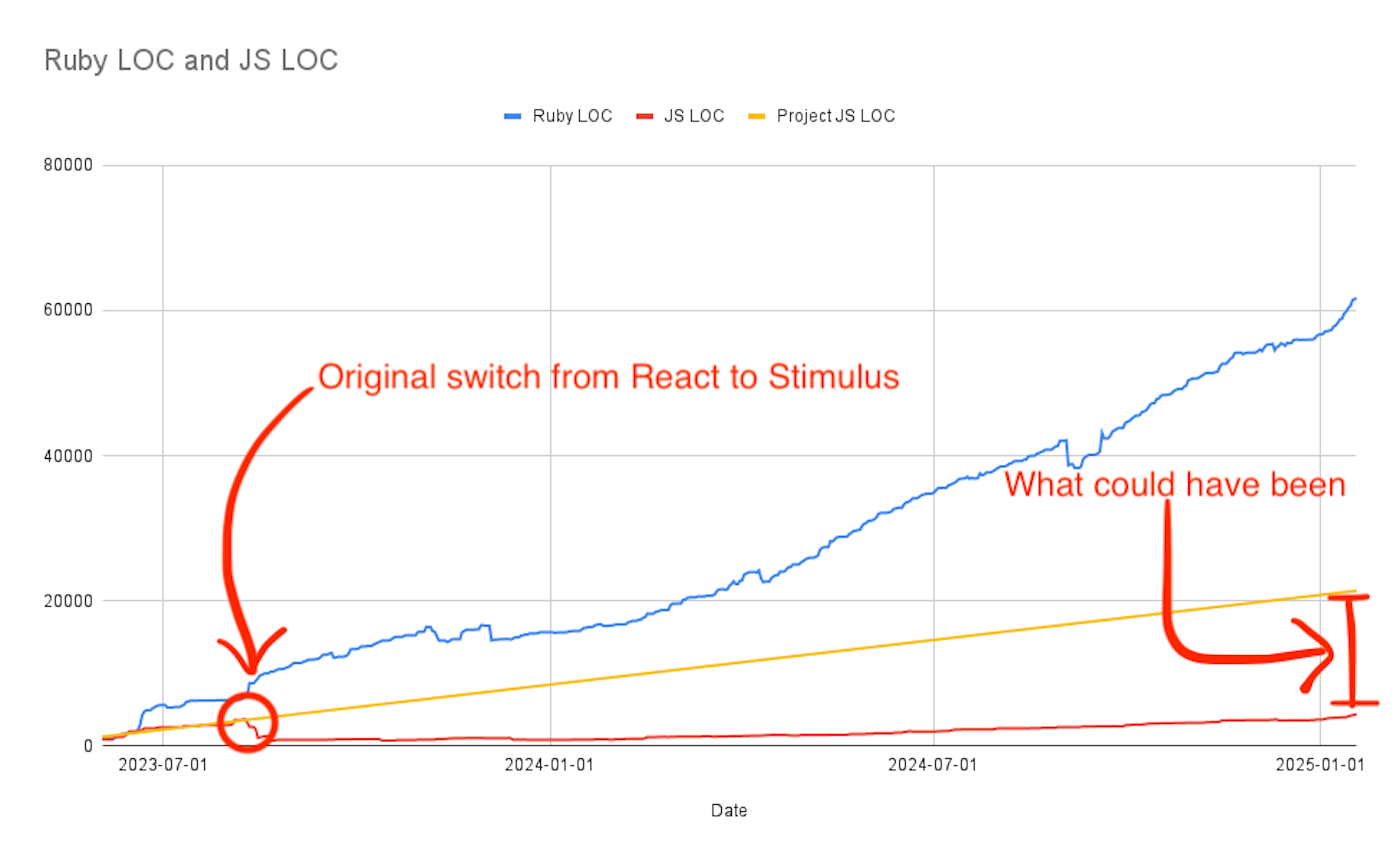

Here’s how our LOC has changed over time:

A few reflections on the numbers above:

- We have 61k LOC of Ruby code and 4.3k LOC of JS

- I’ve added a linear trendline to simulate where we might have been with React. Given my experience with React, this is probably Honest™ for the sake of the argument.

- You can clearly see where we made the cutover from React to Stimulus in August 2023.

- Our Ruby code continues to grow superlinearly, which is expected given the addition of engineers, customers, and features.

- We had 3,690 lines of React code on August 9th, 2023. We didn’t re-cross that threshold until January 3 of this year.

It’s a server-rendered world

Maybe it’s the changing interest rates or political winds, but I think the “fat client” era JS-heavy frontends is on its way out. The hype around edge applications is misplaced and unnecessary for building many different flavors of successful businesses. Many interactions are not possible without JavaScript, but that doesn’t mean we should look to write more than we have to. The server doing something useful is a requirement for building an interesting business. The client doing something is often a nice-to-have.

One of the many ways this matters is through testing. Since switching away from React, I’ve noticed that much more of our application becomes reliably-testable. Our Capybara-powered system specs provide excellent integration coverage.

Because our app is primarily server-rendered and JS takes a backseat role, our system tests flake anecdotally at a much lower rate than other single-page applications I’ve worked on in my career. I’m a little out of the loop, but unit-level testing in JS has always been a bit of a lie: you’re not working with the DOM. If you are, you aren’t seeing the whole picture.

Pushing most of the application logic to the server has made our application more testable at a higher level, without cumbersome client-server orchestration to get the full experience represented in test cases.

It’s really fast

One of the arguments for a SPA is that it provides a more reactive customer experience. I think that’s mostly debunked at this point, due to the performance creep and complexity that comes in with a more complicated client-server relationship.

We work with Nate Berkopec from time to time to help us keep an eye on performance. During one of our sessions with him, we were browsing some of our performance metrics.

When looking at our route change metrics, he didn’t believe his eyes. Our p50 route change time is 86ms over the last month with a p75 at 350ms. This is due to Turbo prefetch in action. Our server response times are reasonably snappy, so by the time a user clicks we’ve already got most of the page.

And best of all, we don’t need to carry the mental overhead of state management on the frontend to enable this experience. Everything is just a page of HTML with some JS sprinkles, so there’s no state to maintain between route changes. There’s no complicated state management on the client.

We view JavaScript as a liability more than most code

Code is not an asset, it’s a liability.

– The wisest programmer probably ever

When we view the lines of code as a liability, we arrive at the following operating model: What is the least amount of code we can write and maintain to deliver value to customers?

When thinking about the carrying cost of different lines of code, maintaining different levels of robust tests reduces the maintenance fees I must pay. So, increasing my more-difficult-to-test lines of code is more expensive than increasing my easier-to-test lines of code.

These liabilities become realized costs when we need to change the code. Change comes with risk, and changing untested code has a higher regression risk. We can compensate for riskier changes with moving more slowly or methodically. Moving more slowly is fine in many cases. But when compared to a world where that change isn’t risky (server-rendered ERB), we are suddenly paying a very pricey tax for making changes in JavaScript.

For a young company it’s doubly expensive: There’s the lost time on the change itself plus the opportunity cost of something else we could have worked on.

Let’s assume that making a JS change costs twice as much time a Ruby change, which I think is being generous to JS. So we can either…

- Make a single JavaScript change might cost 2 units of time.

- In that same time, we could make two Ruby changes (1 unit each), or one Ruby change followed by immediate customer feedback (1 + 1).

- Alternatively, we could make a Ruby change and still have time to sip a mai tai (1 + 1).

The time investment required to safely make changes in a JavaScript application eclipses that of a server-rendered Rails application. This results in a less-competitive business, unhappier customers, and unhappier developers.

Where are we going from here?

Well, we’re sticking with Stimulus and Turbo, that much is for certain. So far, we haven’t come across a scenario where we’ve had to author a worse experience because of these technologies. Our server-rendered, JavaScript-light approach has delivered a faster and more reliable experience. Our engineers love working in this stack as well, often remarking how effective their efforts are.

We’re still a young company with plenty of other existential risks. If we fail, it will likely not be due to our choice of technologies. We can, however, do our best to remove that possibility.

Thanks for reading. Until next time.